Beyond the Headlines: The Truth About UK Waste Exports to Türkiye.

Plastic Export to Türkiye – An Introduction

Plastic export to Türkiye has been in the agenda for any business involved in recycling material brokerage and waste export. Therefore the recent findings from Greenpeace (view the article here) came as no surprise. The provocative headline, “We can no longer bear this load,” accompanied by an image of a worker in full PPE holding up a bag of Tyrrells premium sweet chilli and red pepper crisps, evokes the 2019 images of Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall cradling empty pots of Flora and Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter.

The Greenpeace Perspective

Similar to a recent BBC article on the incineration of plastics, Greenpeace firmly positions itself on the “plastics are bad” side of the argument. This perspective implies that UK waste generators are simply loading containers full of trash and shipping them off to Türkiye. While this viewpoint aligns with the political agenda of an organization like Greenpeace, the reality of waste management is significantly more complex.

Regulatory Landscape

Countries like China and parts of Southeast Asia have implemented strict restrictions on the import of waste plastics from the UK. This is the commercial landscape that any responsible waste broker must navigate. Through close collaboration with partners on both the supply and processing sides, the legal export of commercially viable materials is possible and closely monitored by the Environment Agency.

In Türkiye, the situation is particularly complicated, leading to confusion about what is legal. Initially, Türkiyebanned the importation of goods classified under the local Customs Tariff Schedule 3915.10.00.00.00 (Waste, parings, and scrap of plastics of polymers of ethylene), effectively shutting the door on most waste plastic packaging. However, this decision was softened in 2021, restricting imports to only plastic waste polymer mixtures or plastics produced from mechanical treatment of wastes, classified as European Waste Code (EWC) 19 12 04. To understand more about EWC codes read the following article.

The EU supported this position, clarifying that imports to Türkiye of Y48 plastic mixtures, B3011 PET, PP, and PE mixtures, and plastic wastes containing any polymers produced from mechanical treatment are prohibited. Single-polymer types, such as PVC, may be allowed with prior informed consent.

The Data Dilemma

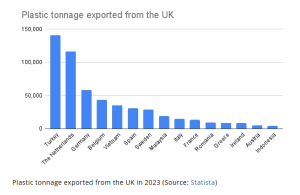

Despite these regulations, data shows that the intended impact is not being realized. Greenpeace highlights a 60% increase in UK waste exports between 2022 and 2023, with Türkiyeremaining at the top of the UK waste export league table.

So, how is it possible that, despite a strict importation ban on mechanically sorted waste plastics, the level of material reaching Türkiyecontinues to grow?

Plastic Export to Türkiye of Non-Mechanically Sorted Plastics

Curbside collections of post-consumer packaging are not the only source of recyclable materials. Material collected at source from commercial settings, such as warehouses and retail outlets, is often separated at the source, negating the need for mechanical sorting. Classified under 15 EWC codes (Packaging, Absorbents, Wiping Cloths, and Filters) this material can be freely exported. However, unless the Tyrrells package mentioned above originated as scrap packaging from the factory, it is difficult to see how it would have reached Türkiye via this route.

Illegal Plastic Export to Türkiye

The most obvious reason for the continued plastic export to Türkiye is that, despite existing laws, mechanically sorted plastic packaging is still being imported. Anyone with a basic understanding of recycling processes can conclude that the now-famous crisp packet did not enter the supply chain without being collected curbside and processed in an MRF.

Since the exportation of a mixture of polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) under B3011 “Green List” requires limited oversight from relevant authorities, the information provided is largely self-regulated.

Conclusion

With UK infrastructure critically underpowered, investment stalling, and plants closing, it is not surprising that exports to Türkiye are on the rise, despite the apparent ban. However, to assume that all exported material ends up dumped or burned does not adequately recognize the large and growing responsible recycling industry in this region. Effective recycling can only be achieved through global circularity, so dismissing a significant portion of the international industry due to a few bad actors will simply shift the problem elsewhere. Legal and compliant waste export to any country willing and capable of recycling it must be supported, often by addressing those who willingly break the law.

In summary, while the challenges of waste export and recycling are complex, it is crucial to recognize the efforts of responsible players in the industry. By fostering legal and compliant practices, we can work towards a more sustainable future for waste management.